BREAKING NEWS

That white balloon was a floating flag of surrender. China was simply acknowledging the American media’s supreme effectiveness in spinning anything the country does into either a military threat, or a sign of imminent collapse.

As a result, it’s now as hard for you to approach China objectively as it was for Chinese to think of the West objectively during the Cultural Revolution.

This is not to admonish, but rather point out the massive asymmetry waiting to be leveraged by a reasonably fair-minded, disciplined investor.

For on one side the world’s second largest equities market hums along, still 80% retail traded by daily volume, still mandated to be a global financial hub, an engine of capital formation for China’s new economy, by a government who, whatever else, is very serious about hitting its long-term targets.

And on the other side: a legacy media raises alarms, mandated to help contain China with its ongoing messaging.

BUT ON TO THE QUESTION

It’s annoying to ask customer support reps a question, only to get questioned back. “Did you restart the machine, sir?” Annoying, but necessary.

Is China investable?

-Do you mean Chinese companies listed in the U.S.? (most investors do) Sure, many golden dragons are still trading at close to liquidation value. But those stocks are most vulnerable to the existential threat of America’s containment-driven policies and China’s willingness to play ball.

-Do you mean buying ETFs? Only if ongoing volatility is factored into your approach. Chinese monetary policy is not designed to ensure buybacks and soaring CAGR. So the CSI300 will not soon be the S&P 500. Then again, the S&P was down 20% in 2022, and optimists will be happy with 4200 by year end. Keep in mind both Vanguard and Schwab are recommending international stocks over U.S. equities. They’re not referring to the LSE.

-Do you mean setting up shop in China and managing your own portfolio? Bold and visionary for non-bulge bracket shops - and honestly, impractical. All the risks concerning opaque regulatory moves and arduous due diligence grow salient in this scenario. Recruiting and keeping local talent will be a time-consuming challenge in its own right.

How is China most investable?

Through active management. As we bid adieu to the golden age of cheap money with modest inflation, and the Fed finds it harder to make hedge funds look foolish, and indexes common sense, it’s going to become ever more compelling to consider paying 2 & 20 for outperformance.

That 2 & 20 goes a lot further in China. The mainland’s top 100 investment shops have deep benches of former bulge bracket pros who saw greener pastures and bluer oceans back home, and came back to conquer. Quant, value, contrarian, the styles and strategies are as diverse as the outperformance is consistent.

At the risk of withering their well-deserved laurels, one dominant theme must be pointed out: these top mainland funds are Mavericks, Lakers, and Celtics playing on what is still essentially a pick-up lot, even if it is the world’s second largest.

WE STILL HAVE QUESTIONS

On to those burning objections to China’s macro-climate that must be addressed. Kindly keep in mind that mainland fund managers do not share the alarm westerners have towards the factors behind those objections.

Instead, much like an experienced pilot, for whom the prospects of turbulence and landing are well-managed processes, but disastrous for a novice flier, such managers have those factors baked into their operations.

Thus we address the macro questions here, not so much to convert the China skeptic as to smooth the path for consultation with mainland managers who want to discuss their latest AI-driven trend signals, rather than when China will invade Taiwan.

So when will China invade Taiwan?

An appeal to a different authority: our founding partner and CIO, Allen Kuo, is also an executive president at China conglomerate Fosun, a long-time resident of Shanghai, and a citizen of Taiwan.

Says Allen, “For investment professionals on the mainland, the consensus is that a ‘hot war’ with America would be economically disastrous, with no clear advantage to victory other than a symbolic one. We believe China’s leadership is also strategic enough to realize this, and as much as possible will avoid a war, while trying to save face and project growing military capability.”

As to the attendant risk, Allen says, “In today’s investment climate, the best way to avoid risk is a Swiss bank account. Of course, the sophisticated investor’s approach is how to price risk. We look at pricing and managing China risk well, as a benchmark for the funds we work with, all of whom boast robust research, liquidity controls, value factors, a whole playbook that’s been working in China for years.”

Increasing government centralization and rhetoric mean growth and development have taken a back seat to political power consolidation, don’t they?

Quite the contrary, paradoxical though it may seem. Consider the following quote from this media brief on the guiding principles of last year’s 20th CPC National Congress:

On July 1, 2021, General Secretary Xi Jinping declared on behalf of the Party and the people that through the continued efforts of the whole Party and the entire nation, we have realized the first centenary goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects.

Building China into a modern socialist country in all respects is the Second Centenary Goal of the CPC. To this end, a two-step strategic plan has been adopted: basically realizing socialist modernization from 2020 through 2035; and building China into a great modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious, and beautiful from 2035 through the middle of this century when China will celebrate the 100th anniversary of its founding.

Yes, the word “strong” was mentioned, but then so was “democratic”. Note well that “prosperous” came first, and consider two statistics:

- Per JP Morgan, as of 2020 41% of China was middle class. Japan stands at 65%; the OECD average is 61%.

- China’s TFP (total factor productivity) is roughly 40% of the American level.

Bringing another 20% of China into the middle class to match Japan’s levels speaks much more to China’s ideas of national rejuvenation than being involved on as many military fronts as America is.

It also puts President Xi’s shibboleth “common prosperity” in perspective: not a Marxist scheme for wealth re-distribution, but an expansion of the middle class, and likewise the domestic consumption so critical to balancing out its over-reliance on exports.

As to TFP, in order for China to double its GDP again by 2035, the Bank of Japan says “To overcome obstacles and proceed with catch-up, China will need to boost TFP growth by promoting innovation and making steady progress in addressing institutional and resource allocation issues.”

Which of the following seem a better approach for China to address those “institutional and resource allocation issues” – moving up the industrial value chain and increasing economic cooperation, or playing the role of increasingly dictatorial, aspiring hegemon that Fox News ascribes to it?

Hey, do you guys still have COVID? What happens if it comes back?

Even the begrudging Bloomberg has described China as having herd immunity to COVID-19. Even if that turns out to not be the case, and another wave of pandemic manifests, the protests and rapid cancellation of lockdown policy in response to them was a watershed event, if little reflected on.

We view it as highly significant that the government responded with quick and sweeping action to the spate of protests, and view it as highly unlikely that it would reverse course and reinstitute extensive lockdowns were a pandemic to reoccur. Hopefully the lack of military response, or further protests once those policies were revoked, will serve to calibrate investors’ views on the extent of the authoritarianism ascribed to the CPC.

China’s aging and shrinking demographics will eventually collapse the economy, right?

Gordon Chang advised of China’s demographic peril in 2001. The return of this narrative, following the failure of the 3 Gorges Dam, 2015 stock crisis, tech crackdowns, or Evergrande’s crash to collapse China’s economy, lead us to believe that this demographic ‘crisis’ is a filler narrative until something more substantial heralding China’s collapse appears.

The question is if China is growing old faster than it is growing rich enough for the increase in spending on senior entitlements, and innovative enough to increase productivity to the point that the dwindling number joining the labor force can be offset.

One may point out that Americans over 65 are 17% of the population to China’s 11%, or Japan’s comparably low fertility rate, yet both these countries became advanced first world economies before facing these challenges. Still, given their debt levels and other economic challenges, it would be biased to assume demographic issues will have a larger or more negative impact on China than on America or Japan (or Germany), and ultimately unreliable as an investment theme, given the number of unwieldy inputs.

Hereon, the macro context addressing other concerns, which caused many to label China "uninvestable". We hope our brief unpacking helps inform an approach to more accurately access and price the risk associated.

CHINA MACRO CONTEXT I: CRACKDOWNS: SOWING SEEDS OR SALT?

The well-publicized crackdowns on Ant Financial, Didi, & Chinese education companies were neither as peremptory nor as anti-capitalist as the mainstream narrative would have investors believe. This is not only our considered opinion, but also that of Goldman Sachs analysts, Bridgewater Associates, and the overwhelming consensus of fund managers and other institutions we are in contact with here in China. As to the latter, we refer to our off-the-record conversations with executives at institutions such as Haitong Securities, CICC, and Diligence Capital, not what is printed in Chinese media organs.

Best-practice thinking requires considering events from different viewpoints. Thus, while we can well understand the considerable dismay the crackdowns stirred in near-term views of China’s investability, we deem it necessary to concisely lay out reasoning as to why they constitute mid and long-term positives.

Ant Financial: Revenge of “the Pawnbrokers”

We certainly don’t condone the suppression of free speech. But the least degree of prudence for doing business in China requires curtailing public criticism of its government. Jack Ma’s failing to do so at the Shanghai Bund Summit, and his frightening personal consequences, grabbed most of the headlines in the subsequent suspension of Ant Financial’s IPO, and eventual reformation under China central bank guidance.

Less well-publicized are the facts that by the time of the crackdown, Ant had originated loans for over half a billion borrowers totalling at least $230b, originated through over 100 banks. These banks were all smaller institutions with relatively weak risk controls, and thus more willing to expand their balance sheet through Ant’s lending platform, Jiebei, “just borrow”. Jiebei offered unsecured loans for general purposes, trusting borrowers to obey consumer lending laws that prohibit the use of those funds for business purposes.

Given the pre-public size and metrics of Ant Financial, and the proliferation of other digital lending platforms, it is little wonder that Chinese financial regulators had been formulating tighter rules guiding their operation months earlier, declaring that a new regime would be announced in November, the same month that Ant had planned to go public. The persistent problem of hidden and bad debt at all levels of China’s banking industry should make plain the government’s apprehension at the added systemic risk Ant Financial would incur.

Most germane to our overall argument: while members of newly-formed Tirith were participating in the Ant Financial pre-IPO frenzy, they were also getting wind of the potential government blowback from astute local money managers, who make government policy review a daily practice.

Didi: The CAC Strikes Back

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) had been raising questions about the security of Didi’s network weeks before the “Chinese Uber”’s IPO, even suggesting the company delay listing further to an internal security review. The suggestion should have been heeded in the context of the new, typically vaguely-worded cybersecurity law adopted a month earlier.

But Didi’s was a U.S. listing, where the CAC had never intervened. And Didi executives claim they were never “explicitly” warned, although they declined to ring the bell at their successful debut, or publicize the event on their social media channels.

More important than circumstantial evidence pointing to Didi execs’ letting greed overcome good sense in not delaying their IPO, is the question of risk. We ask rhetorically for permission to invoke the “shoe on the other foot” argument. Would the suspension of an American app that stored the data of millions of users without clear security procedures, which had just listed in Hong Kong, be automatically and widely condemned as “anti-capitalist”?

Consider in tandem the U.S.’ previous de and re-listing of three Chinese telcos with purported ties to the Chinese military. Then consider the fracas and resultant price volatility over TikTok, Tencent, and Huawei. Do only American concerns for national security outweigh short-term stock gains? Lest we seem to be straying too far from objectivity, let us again recall our theme of risk management, and report that the same policy-minded financial professionals who declined transacting in Ant’s pre-IPO offers, also warned of Didi’s vulnerability well prior to its listing and app-suspension.

China’s Education Crackdown: Leave Them Kids Alone

It’s easy to understand the shock caused by China’s bestowal of non-profit status on listed education companies. It’s also high-time we moved on to outlining China’s very clear plans for transforming its economy by a decidedly capitalist long-term plan for its financial markets.

So as simply as possible, there is decidedly an element of resistance to western influence in the crackdown on English tutoring institutions. But xenophobia is hardly the driving motive, much though Fox News would like us to believe so.

Rather, it is one of widening social inequality. The consequence of Chinese parents’ dedicating every resource to their children’s success on standardized tests has driven the proliferation (and moral hazard) of China’s private test-prep industry. The unintended consequence is that only families with the resources for such tutoring have a robust chance of seeing their children matriculate into the woefully limited number of good Chinese university seats. As evidence of the growing-inequality driver, please note that the schools forced to register as non-profit were those teaching core subjects on China’s all-important gaokao, the college entrance exam*.

For some extra context, one might consider a new law placing responsibility on parents to ensure that their children’s studies are balanced by ample rest, play, and exercise*.

More importantly, please note that Tirith portfolio manager Wellspring Capital followed China policy closely enough, and had a risk-management policy tight enough, to divest from all China education stocks a full year ahead of the “sudden and peremptory crackdown.”

TAKEAWAYS:

The foregoing could easily give the impression that we are armchair economists with a pro-China agenda. Far from it! We are investment managers with a pro-China agenda. Not pro-China in the sense that a Fox news analyst or CIA director would deplore, but rather, hopefully, in the sense that Ray Dalio would approve: acknowledging the many risks and challenges of China’s investment landscape (explored below), but overall convicted on its long-term growth potential, and suitability as a diversification play.

Thus without further ado, our takeaways from the crackdowns:

- S-listed Chinese companies are particularly vulnerable to further China government crackdowns, particularly companies large and disruptive enough to pose threats to China’s security and/or economic stability. Although they and Hong Kong securities are what’s commonly meant when referring to “Chinese stocks”, it is high time for more institutional investors to consider domestic stocks.

- It is best to be risk-off on sectors that China’s government perceives to exacerbate inequality, such as education and housing. Which brings to mind Evergrande, which we’ll add to this article in a few months, when the dust has settled, but which we predict will fall far short of the “Lehman Brothers moment” disaster forecast by mainstream media (as of writing, September ‘21).

- While it’s impossible not to ascribe an element of tit-for-tat, if not outright revenge, to China’s crackdowns, examination of publicly-posted policy makes plain that national security, economic stability, and social equality were far more important considerations.

- A risk-management style that includes regular perusal of China’s publicly available policy updates, and prompt action, greatly reduces chances of being in positions affected by “crackdowns”.

Granted, extenuating moves beyond short-term financial losses, such as curtailing online gaming hours, quashing “effeminate” male performers, and disappearing celebrities critical of the CCP, may smack of an environment so draconian as to make long-term capital market growth unlikely. Thus our next section presents macro trends that more materially influence the eminent question of China’s investability.

CHINA MACRO CONTEXT II: ECONOMIC GROWTH: PAST, PRESENT, & FUTURE

We’re the first to recognize the futility of macro analysis for predicting short-term security or market pricing. However, our purpose is to assess the prospects of China’s capital markets long term. It is that purpose, rather than political advocacy, that excites no little appreciation for the long-range planning capabilities of the CCP, and the cohesion that increases its chances of carrying out such plans.

In broad terms, it is hopefully not too inflammatory to acknowledge that, in terms of economic planning, China’s socialist government has absorbed the very painful lessons of its early history, and stresses cautious, judicious application of economic policy as an overarching mandate. This is not to disregard the corruption or lack of transparency that has and could continue to result in significant crises on both a general and acute level, as in its ongoing debt crisis, and the resultant Evergrande collapse. It is also obvious to us that a central governing body with no predetermined checks or balances will result in capital markets constrained and shaped by that fact.

Having said that, and to continue on broad terms, so as to present our general thesis: after roughly two decades of experimenting with market reform, China joined the WTO in 2001. Its stated goal was to become a globally significant economy, although that economy at the time was equal to Argentina’s. It became the world’s second largest economy just ten years later.

Due to a combination of external and internal pressures: trade wars, slowing growth, and a dawning cold war, China is committed as never before to transforming into a fully-developed economy*. Furthermore, it has publicly stated that a key driver for this transformation will be its capital markets, with attendant long-term plans to transform them into a global financial hub*.

Looking back, it is easy to frame China’s economic ascendancy as a fait accompli from WTO inception. But we remember the bears who predicted the end of that trajectory at every crisis, The Coming Collapse of China, the imminent bursting of the real estate bubble, the inevitable government collapse in the wake of increased prosperity.

Looking forward, we find it far less easy to lend credence to the bears, who are now calling the aforementioned crackdowns proof positive that China is “uninvestable”. Having looked at the plans and policies, we find it easier to believe that China can and will manage a slow and unique evolution into a developed economy, boasting internationalized capital markets as a corollary.

Such a belief runs contrary to the prevalent theme that China is first and foremost a socialist country, and that authoritarian measures to maintain that fact, as well as constant fear of public unrest, will limit its markets’ development. It is an understandable viewpoint, but one with which we disagree, pointing to the past thirty years of market reform, the increasing sophistication of its stock exchange and capital markets, and most importantly, our view that the communist party bases its legitimacy on driving economic progress.

Thus we turn to the three synergistic factors that we see driving China’s long-term transformation, then the challenges, before addressing China’s domestic markets, and how best to capitalize on them.

CHINA CONTEXT III: PURSUING INNOVATION, SELF-RELIANCE, & COMMON PROSPERITY

EVERGRANDE: COLLAPSE, OR CONTROLLED DEMOLITION?

Note: This section is being added as 2021 comes to a close, and almost three months after this article was first published.

We have watched as the western media terrified audiences by implying the impending default of the bloated real estate developer would almost certainly be China's "Lehman moment", and had every possibility of setting off a "global contagion".

Throughout the hype cycle, we held to our viewpoint that, while certainly painful, and not to be easily contained, that the default and/or bankruptcy of Evergrande and other perilously overleveraged real estate developers was foreseen by central planners.

This view was neither prescient nor naive, but rather a simple observance of preceding policy. The previous year, 2020, saw the government's drawing of "The Three Red Lines", new rules limiting debt ratios. That year also saw a record number of Chinese corporate defaults. Thus, when Evergrande's impending collapse hit the press, we were not asking questions such as "Will this be China's Lehman moment?", but rather,

"Do people think this is a surprise to the financial planners who mandated the 'Three Red Lines'?"

"Who on earth is holding Evergrande paper, after those lines were drawn, and there were a record number of corporate bond defaults?"

We will hopefully not be thought smug or self-aggrandizing to report that all of Tirith's portfolio managers - MegaTrust, China Future Capital, and Chongyang Capital - were well out of related securities months in advance of Evergrande's western news debut. None of these managers are crowing about their prescience, mind you. It was simple policy observation, prudence, and standard risk management.

DEALING WITH EVERGRANDE: NO SOCIALISM FOR CEOs

As Evergrande's collapse failed to live up to its potential for terrifying news ratings, the new mantra became "Too big to fail." Surely the government would bail out Evergrande and other sinking real estate ships, and let the taxpayers pick up the tab for this "unforeseen" disaster, basically the Fed playbook after the real Lehman moment.

Instead, the government held CEO Hui Ka Yan's feet to the fire, forcing him to use personal assets and sell shares, while ensuring that the thousands of families who had put deposits on yet-to-be-built apartments would not be left in the lurch. True, Evergrande has missed payments to bondholders, a tough lesson for whatever analysts and investors decided that the company's obviously high-risk profile was in line with the yield.

Now that the default of Evergrande and similar bloated real estate conglomerates are obviously not going to collapse China's financial system, let alone its economy, our thesis that the crisis was foreseen and planned for doesn't meet with as much incredulity.

But there there is always a pronounced will to count China on its way out. Currently, the long-denied anticipators of The Great China Collapse are positing that, with so much of China's wealth tied up in real estate (upwards of 70%, by some estimates), that there can be no controlled landing, and that reduced home sales and real estate taxes to local governments, among other impacts, will crash the economy.

In the meantime, central bankers are lowering reserve ratios, and taking other open market measures to increase liquidity, but maintaining a comparatively (to the West) tight credit policy. We are also noticing a pronounced drive to diversify wealth into equities holdings. Since the Tirith team has been collectively, and correctly, poo-pooing China crash predictions since 2005 (and correctly calling the 2015 bubble, a no-brainer), we like to think our thesis that China will ride out its current real estate woes, albeit with slower growth and other consequences, is not received as too biased.

Our macro takeaway from Evergrande, however, is China's fundamental emphasis on long-term stability and broad prosperity, rather than unwieldy growth for an ever-thinner slice of its population. We can only wonder, upon learning that U.S. home prices shot up more than 18% this past October, what the reaction would be were President Biden to echo President Xi and declare, "Houses are for living in, not speculation."

INNOVATION:

While we are well-apprised of the world’s myriad crises, and their ramifications for the global economy, we also see a coming wave of increased productivity and value creation world-wide, fostered by well-discussed technologies whose impact is still largely nascent: DNA sequencing, Robotics, Energy Storage, AI, and blockchain. The impact of their development will scale to greatly disrupt the models of many global corporations, and have a largely deflationary impact.

Obviously, their development will include the formation of scores of new companies that will eventually go public with $1b+ valuations. We believe a great proportion of those companies will be Chinese. To take AI as an example, China’s leadership in patents and research patents does not necessarily translate into a “real-world” advantage. However, its demonstrated pattern of leveraging “catch-up cycles”* to create domestic versions of first-mover tech giants: Alibaba vs. Amazon, Didi vs. Uber, etc. should continue into these fields of emerging tech, given the increased amount of R&D spending and government support*. There is significant opinion that China is actually leading on AI and telecommunication fronts, for that matter.

So as to the well-worn “copycat China” trope, which admittedly we paid lip service to as late as 2014, it is past time for investors to incorporate the country’s history of R&D theft and forced technology transfer into a broader narrative, one that includes its strides ahead of the West in digital payment and ecommerce platforms, and acknowledges China’s space program going from strength to strength, despite its exclusion from the International Space Station.

Our personal past involvement in raising VC for tech startups in Beijing and Shenzhen, two of the world’s top-five technology clusters, bolsters our confidence that China has the talent and drive to become ever-more-innovative. Its number-twelve ranking on the Global Innovation Index*, ahead of Japan, Canada, and Norway, lends more objective support.

In sum, we see China as very well-positioned to capitalize on the coming wave of emerging tech and its corresponding value creation.

SELF-RELIANCE:

If we have previously veered too close to the politically-biased so far, in order to make our case for China’s investability, then let us make a clean breast of it: we don’t believe in national rivalry or ideological supremacy as inevitable, necessary evils, and view the best path forward as one of increasing interdependence and cooperation. This certainly colors our mission in building a platform by which foreign investors can seamlessly deploy China domestic stock portfolios, hoping that increased financial interdependence props up a broader consensus for peace.

But for the time being, China views its realpolitik dynamic as one demanding increasing technological independence. Most famously, a marker of this independence will be its capacity to produce microchips at scale. But that drive to independence also encompasses aforementioned emerging tech, such as AI technologies for security, and blockchain technologies such as its digital yuan. Advancement in 5G and cloud computing ramifies from these concepts.

The Chinese government is well aware that efficient capital markets are crucial to growing innovative companies into mature organizations that will empower the desired degree of tech self-sufficiency. Such awareness is evident in last year’s streamlining and simplification for companies seeking to list on Shanghai’s Star Market and Shenzhen’s ChiNext boards. These new bourses are meant to evolve into domestic versions of NASDAQ, and spur a new tide of economic growth. Despite our commitment to risk-managed processes, and the significant volatility we anticipate on these new boards, we are likewise excited about the corresponding growth of China’s opportunity set.

Of course another key pillar of increased self-sufficiency involves the maturation of its domestic economy. The impetus to balance its export-led GDP with a thriving consumer economy, replete with a gamut of add-value services, has increased in response to the prospect of increasingly fickle trade partners, if not outright sanctions. Hence, there is a new focus on increasing domestic production of agricultural, medical, pharma, auto, tourism & culture-related products, which we believe will be reflected mid-term in overall domestic stock growth.

Of course, another motivating factor is recovery from COVID-19’s ongoing economic drag. China’s singular efficiency in an orderly economic rebound from the height of the global pandemic, gives us reason to believe that China can make progress on its path to greater self-sufficiency, and largely agree with McKinsey, who is calling Chinese consumers “the growth engine of the world.”*

Where others hope that engine has intakes for increased imports, we see it driving the growth of domestic consumer companies in tandem, from the aforementioned focus sectors, to the multifarious online shopping services evolving to meet the times.

COMMON PROSPERITY:

As this is written, Xi Jinping’s calls for broader prosperity in China are being framed in the context of Alibaba & Tencent’s sizeable, ostensibly coerced donations to the cause. While we agree random extortive charitable contributions are deleterious to a company’s short-to-mid-term growth, we find it hard to believe such contributions will continue in an unsystematic manner, if at all.

Furthermore, we find the frequently-voiced fear that those donations point to an imminent Marxist redistribution of wealth lamentable, if not laughable. The plan to reduce income inequality and broaden China’s middle class is a nuanced one, guided by officials far too experienced, educated, and prudent to fly in the face of their long-term goals to revisit failed communist experiments.

Some comments from the recent meeting to address the theme of Common Prosperity, by the Central Commission for Financial and Economic Affairs’ (CCEFA) Deputy Director Han Wenxiu, as translated from the readout of his briefing:

- “We must create more inclusive and equitable conditions for the people to improve education and development capabilities.”

- “We must open up channels of upward mobility, create opportunities for more people to become rich, and form a development environment with participation from everyone.”

- “We must encourage hard work and innovation as a means to wealth.”

- "[China must] guard against falling into the trap of welfarism.”

Instead of revisiting failed Marxist experiments, the plan, as concisely as possible, is to a) expand the middle class by increasing incomes, particularly of the 600m Chinese who make $150 per month or less, through urbanization and agricultural upgrade, b) encourage more spending by making healthcare, education and housing more accessible, and gradually increasing social security services. There will also be increased taxation for China’s wealthy, most likely in the form of capital gains taxes.

Digging into the myriad implications for China’s economy as it pursues these goals is beyond the scope of this treatise. Higher taxes on China’s wealthy alone would serve as an apt topic for potential effects on capital formation, or capital flight. Instead, we’ll go on to broader challenges facing China in pursuit of these goals, after this section’s takeaways:

Takeaways:

- China is positioned to lead in and benefit from the growth & value created by emerging tech, growth and value which will be reflected in China’s new NASDAQ-style boards, and later its broader markets.

- The drive for increased domestic consumer supply and demand will likewise be reflected in the growth of China’s capital markets.

- The call for broader prosperity is not a dog-whistle signalling income redistribution, but rather a cautiously accelerated impetus to increase China’s middle class by increasing incomes, particularly those of its 600m citizens living on $150 or less per month. Defense of the one-percent’s bottom line will not be nearly as vigorous as it is in America, however.

CHINA CONTEXT IV: ECONOMIC CHALLENGES & SOLUTIONS

Please note that our intent is not to construct an exhaustive analysis of China’s vast economy and the many dynamics shaping it. Rather the goal is to provide our reasoning as to why we believe China’s domestic capital markets will see robust growth, internationalization, and opportunity for diversification over the long term. It is in this light that we have addressed the regulatory crackdowns which have so spooked investors, the investment context in terms of China’s recent history, aspirations, and now the key challenges to such growth.

DEMOGRAPHICS:

Currently, the demographic crisis in focus is slowing population growth. True, the government fears a shrinking work-age force supporting a growing population of retirement-age citizens requiring underfunded social health services.

This problem is certainly not unique to China. From an economic standpoint, we see the unique challenge to China in that, unlike other nations with aging populations and lower proportions of working-age citizens, it has not become “developed nation rich” before growing older. Therefore, we see productivity as an overlooked, but under-scrutinized variable. China’s productivity is notoriously inefficient, and improvement has slowed since the GFC in 2008*.

While we factor in weaknesses such as its non-international services sector, and the still weighty role of SOEs, we see the relatively high productivity, for its income level, of China’s industrial sector, particularly in the efficiency with which it is upgrading to high-tech manufacturing. This brings us again to our theme of new economy, our belief that emerging technology will be disrupting old value chains and creating new wellsprings of growth. We believe that, given China’s emphasis on STEM education, and willingness to invest in new tech initiatives, such as highways dedicated to automated trucking, that it is positioned to harness the resultant productivity, and manage its aging population without broad-based economic contraction.

DEBT:

Let us reiterate that we do not attempt to downplay the challenges facing China, only to provide the highlights to a more nuanced view at odds with the mainstream narrative, and which we feel proves that China’s true stock market, rather than NASDAQ or Hong Kong listed, is eminently investable.

Thus at a macro level, we can point to a range of considerations from the government’s efforts to deleverage following the COVID-induced liquidity of 2020, to Evergrande’s continuing aftershocks, despite the distinct lack of “global contagion” so vociferously feared but recently. Then again, the subject of debt at the domestic and foreign level, from public to foreign to household, comparative to global benchmarks, and resultant predictions for long term effects on the capital markets, is a project that Noriel Roubini himself would quail at.

We find it much more efficient to rely on proven global teams putting money behind their convictions, to gauge best whether China’s debt issues will provide head or tailwinds to its capital markets. As far as debt is concerned, we look to their opinions on China’s bond markets:

- Blackrock’s Head of Asian Credit has a positive view of China’s domestic bond market.*

- P. Morgan’s Chair of Global Research, a China bull, although recommending sidelining investment in China indices for Q4 ‘21, recommends bonds as a safe strategy for exposure to China’s economic growth.*

- Rowe Price’s Head of Fixed Income is also bullish China bonds, citing pandemic recovery, deleveraging process, relatively high yields, and non-correlation as key factors.*

We presume to extrapolate that these global giants’ positive stance towards China’s debt markets, have in their calculus factored the risk of those economy-plunging debt crises warned of by Reuters and Bloomberg, and the massive market corrections which would follow, and found it decidedly less than significant.

Finally, we take FTSE Russell’s imminent inclusion of Chinese sovereign bonds to its World Government Bond Index as a deciding factor in our conviction that China can deal with its debt challenges in a manner that supports capital market growth and stability.

TAKEAWAYS

- Although not in the same high-GDP bracket as many other aging countries, China is implementing long term strategies for making its population and economy more productive, in marked contrast to countries facing similar challenges.

- While Evergrande’s collapse still makes headlines, albeit proving “contagion” predictions unwarranted, global leaders in fixed income are bullish on China’s bond markets, and by inference China’s ability to meet its debt obligations.

CHINA’S A-SHARE MARKET: AN UNVEILING AND OVERVIEW

Before an overview of China’s A-shares composition, we’d like to first identify characteristics that make it both an attractive candidate for investment diversification, as well as having the potential for mid to long term outperformance through active management.Then we will look at its key risks, before describing its historic performance and composition, and compare it to other markets.

Beyond Baba: An Overlooked Opportunity

The fact that, until recently, mainland Chinese stocks have been available only to the biggest foreign institutions, explains why the mainstream narrative has so many convinced that Chinese stock performance is all about Alibaba, Tencent, or other relatively well-known U.S. and Hong Kong-listed securities.

In the meantime, consider that the China A-shares market, comprising public equities traded on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges:

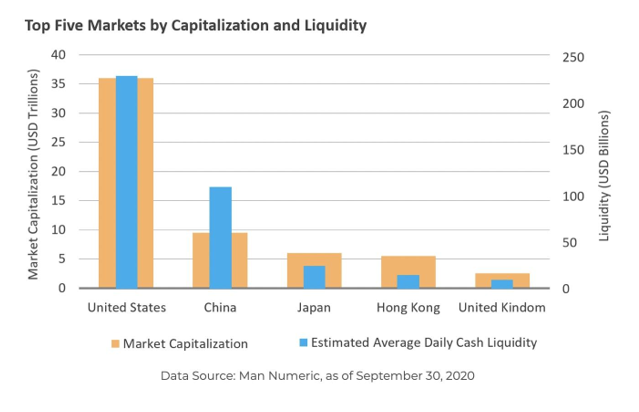

- Is the world’s second largest, with a market cap of approximately $12.2 Trillion, as of 01/21.

- Is the world’s most liquid, with bid/ask spreads half the U.S. median, and median daily ATV far above that of other markets, with turnover velocity five times that of the Hong Kong and London’s exchanges

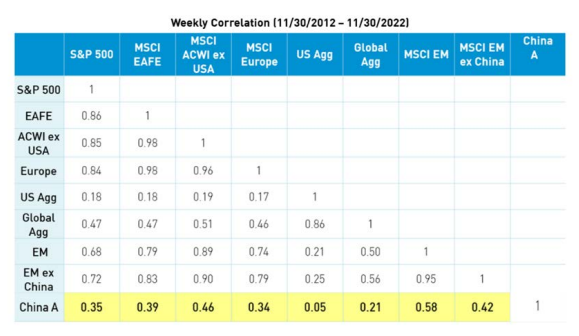

- Is by and large uncorrelated with American and European equities (see chart A)

- Constitutes less than a percent of global institutional portfolio holdings, while foreign ownership (including Hong Kong) constitutes approximately 4.3% of market cap

- Retail traders are approximately 80% of daily volume, resulting in significant inefficiency and volatility, with attendant risks and opportunities.

Thus the potential strengths we see in an A-shares allocation:

- Participation in a large (and growing: see chart B) and liquid market, virtually ignored by global institutional players

- That large and liquid market’s lack of correlation to North American and European markets constitutes true equities diversification

- The relative lack of disciplined, professional investment teams in the market, and preponderance of retail traders investing primarily with amateur technical strategies, creates an inefficient market, and potential reservoir of alpha for good active managers

As to constituents, although 80% of A-shares’ market cap is owned by institutions, retail traders account for 80% of the daily volume. There are more than 500m trading accounts open in the PRC to trade onshore stocks, due to the flywheel promotional effect of bank and lending platform products. This anomalous structure goes far in explaining both the market’s inefficiency and volatility, as well as pointing to opportunities for outperformance. (insert trading account chart)

CONSIDERING A PASSIVE INVESTMENT APPROACH

The Limitations of Hands Off in Hong Kong

As purveyors of an actively-managed solution for institutional investors, our bias to such an approach is obviously baked into our views on passive exposure to onshore China equities. Then again, part of our impetus for launching Tirith Capital sprang from the shortcomings and limitations we saw in passive strategies.

For instance, we viewed the MSCI’s growing weighting of Chinese stocks in their emerging market index as a positive sign overall. The index, and correspondingly the many index products which track it, are what we would consider overweight in U.S. and Hong Kong listed stocks. We consider such broad exposure sub-optimal, given the focus on low-growth large and mega cap Chinese companies, and the fact that companies on U.S. exchanges are now under scrutiny for their VIE structures, and at risk from both potential U.S. and/or China government intervention. Heavily foreign-invested tech giants with access to private citizen data , and the power to impart systematic risk to China’s economy, logically bear the brunt of the “uncertainty” which is unfortunately imputed to the entire China stock universe.

To put it another way, passive exposure to the entire universe of Chinese stocks does constitute diversification of the broadest sort, but by no means the smartest. We know as well as any financial show pundit the weighty role China’s government plays in a Chinese company’s long-term prospects. However, we see both the positive and negative aspects of this reality, and recommend focus on the opportunity set that has the full and active backing of related China government bodies. Besides the aforementioned emerging tech sectors, we would add companies which speak to China’s mandate to be carbon neutral by 2060, and its support for alternative energy.

Does this mean that the onshore market, mandated though they it is for overall growth and evolution, is free from systematic risk, risk distinctly different from that of western markets, and therefore more difficult to adjust for? Of course not. Thus do we view passive investing through the Stock Connect program an incomplete solution, for those seeking diverse, and truly risk-managed China exposure. True, even though only eighteen hundred A-share stocks are available through Stock Connect, a third of the total available, they represent 80% of market cap. However, the program amounts to accessing the markets through a prime broker in Hong Kong, and thus has some attendant limitations and risks of its own:

- No day, turnaround, or manual trades

- Maximum order sizes of one million shares

- Forced sale of shares if foreign investors exceed 10% of a company’s outstanding shares

- Non-transparent pre-settlement, four-hour settlement window, and single-sided settlement details incur outsized settlement risk to the buy-side, in the event of trade mismatches and exceptions

OTHER RISKS IN CHINA’S DOMESTIC MARKETS

In big-picture terms, of course, the greatest risks are systematic. The escalating tensions between China and America, and the promise of ever-tightening regulations in multiple business sectors are not to be taken lightly, however optimistic we are about overall long-term prospects for China’s economy and capital markets.

Crackdowns

Without returning to an extended macro unpacking, we see the recent spate of “crackdowns” as largely indicative as a desire to manage systematic economic risk, and prevent tech monopolies that could prevent sector growth by barring smaller players. Despite the disconcerting swiftness of the measure enacted, we reiterate that public policy warned of the possibility of such measures. When taken into the broader context of China’s stated and evident need to drive its new economy through financialization, we feel “crackdown” risk can be accounted for and managed in an overall China portfolio strategy.

Suspensions

As the broader perceived policy risk of China’s new Common Prosperity Initiative has been addressed above, let us address a demonstrated historic risk: stock suspensions. It would be unwise to discount the China market crash of 2015, when a 30% drop led to the suspension of over 1,500 stocks, some of which remained inactive for close to a year before trading resumed*.

That precedent, and continuing levels of suspensions higher than that of other emerging markets in general, weighed heavily in the MSCI’s hesitancy to include A-shares in its indices. China’s government pledged to address the issue, with results that have recently been put to the test: in 2020, as markets plunged again, the number of stocks suspended were under 0.5%. Therefore, while we would not presume to discount the prospect of suspensions above that level in a subsequent market correction, especially one sharper than that brought about by the COVID pandemic, we do not weigh the risk nearly as heavily as we would have from 2015-2020.

Governance

Much is made of China’s opaque accounting practices, with good cause, historically. Business regulations, needless to say, can also be modified without the robust means of recourse available in other countries.

Reassurances of changing standards mean little without corroborating evidence. To keep things concise, we’ll point to the financial statement metric most relevant to investors - earnings. It’s common to encounter the perception that publicly-listed companies can fudge their earnings without undue cause for retribution, perhaps under the impression that China market regulators are beholden to an unspoken mandate to prop up market cap and valuations.

Such views are held in ignorance of regulators’ decidedly paternalistic approach, which views avoidance of pump-and-dump schemes, and resultant scandals, as high a priority as stable growth of the market. Therefore, corporate earnings are of significant interest to regulators, to the extent that sudden declines in earnings are seen as a cause for investigation, if not delisting, should the trend persist. As a result, there is a trend of Chinese public companies actually under-reporting their earnings, and holding some relatively liquid assets in reserve, should they be needed to demonstrate stable, steady growth to those regulators in audited reports.

Therefore, while transparency at the corporate transaction level remains significant, with attendant risk, we know that the better portfolio managers have access not only to the financials submitted to China’s securities regulators, with extreme penalties in event of discovering bad faith, but also important data that is not necessarily included on financial statements. This fact bolsters our recommendations for an active approach to allocating to A-shares, detailed below.

Lack of Hedging Options

Traditionally, onshore China hedge funds have not even been hedge funds in that they were exclusively long only, due to the lack of sophisticated financial products with which to hedge.

Shorting was allowed, but without a robust regulatory framework in which the government reserved the right to step in and cancel transactions. So aside from switching to cash, portfolio managers were generally limited to vanilla futures and options linked to China indexes.

True to our thesis that China is truly committed to liberalizing and reforming its markets, in 2020, the China Securities Regulatory Commission allowed QFII and RQFII (RMB) investors access to China’s five onshore derivatives markets.

CONSIDERING AN ACTIVE APPROACH TO CHINA A-SHARES

The risks above, in tandem with the limitations of passive investing in A-shares as it now sits, are why we espouse active management by proven top performers, such as our partners at Wellspring Capital, the aforementioned managers with the foresight to exit education stocks in 2019. Of course, considering that the average portfolio manager in China has 2.6 years’ experience in the industry, accessing best-of-breed management is easier said than done.

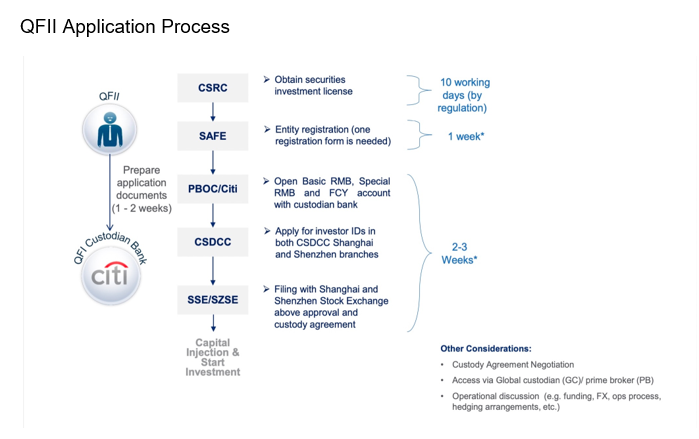

New QFII Regulations: Easier Done Than Said

Investing directly into China A-shares requires a QFII license. For most of China’s Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor program history (set up in 2002), the license was only granted to the largest banks, with strict quotas and other limitations. True to their long-range plan of internationalizing and evolving their capital markets, China greatly relaxed both its application standards and scope of investment further to granting the license.

Currently:

- The minimum AUM and years of operation as an investment organization have been removed as qualifiers for eligibility

- Alternative asset managers are now welcome to apply

- The previous 25 documents required have been reduced to 4

- Investment quota restrictions have been abolished, including minimum injections

Besides buying and selling stock positions, investment scope has been expanded to include:

- Margin financing, securities borrowing & lending

- Commodities funds

- Private Investment Funds

- Depository receipts, repos, & shares transferred on NEEQ, Beijing’s New Third Board for high-growth innovation enterprises

- Issuance of stocks, bonds, and ABS

As to “money out”:

- No restrictions on repatriation of either principal or profit

- Free to do repatriation for net redemption purposes, as for an open-ended fund

- No capital gains tax on profits

Below is the QFII application process as handled through our partner CITI, who maintains a 100% approval rate for clients.

Beyond Licenses: Components of Direct, Active Investment

After mentioning active management, let us briefly consider what is necessary for an asset manager wishing to take a hands-on approach to China’s A-shares. We’ll leave aside the nominal costs, other than setting up a WFOE enterprise (approx. $2500), an office (average Shanghai grade A office space rents for about $4.50/sq ft monthly), or an administrative professional (approx. $20k yearly).

Instead, we’ll look at the providers necessary to establish a portfolio with standard processes:

Custodian: A relatively simple step, for which we recommend our provider, CITI, a standout in terms of experienced, helpful team, and comprehensive services.

Auditor: Also straightforward, as household names such as Ernst & Young have dedicated departments for auditing securities portfolios.

Prime Broker: Essential to hedging and risk management, as well as making larger trades efficiently, a good relationship with a prime broker is paramount. This can present a challenge to a new, and especially foreign investor. Standout prime brokerages such as those of CITIC, HSBC, or our partner, CICC - have limited bandwidth, due to their reputation, high demand, and relatively small number of mainland prime brokerages offering an international level of service.

Execution Broker: Unlike many countries, China does not permit prime brokers to also execute trades, hence the need for an execution broker. True, there are several banks that will perform these services and others as a one-stop shop. However, our experience with such institutions has led us take the trouble to separate the processes, for the sake of cost and efficiency. We recommend anyone serious about securities trading in mainland China to do the same. As with prime brokers, knowing the right person at the right place will result in both a qualitative and quantitative improvement in execution. For example, issues in order compliance tend to arise more frequently than western investors are used to, making smooth and rapid communications with one’s executing broker a must.

Onshore Advisor: The issue of finding and vetting brokers can be offloaded to a good onshore advisor, who will provide these channels and others, as well as compliance procedures for injection of capital into vehicles and related matters. On the other hand, an onshore advisor will charge varying fees and carry costs, generally in inverse proportion to the size and reputation of the incoming investor. That onshore advisor might also not be able or willing to provide the best channels to a new investor.

Private Fund Management License: Obtaining a PFM license obviates the need for an onshore advisor, but requires lengthy application procedures, and the allocation of substantial amounts of capital, to the extent that our partners at Fosun International declined to pursue one, preferring the advantages of separate prime and execution brokers, and an independent onshore advisor.

Portfolio Manager: Foreign institutional investors looking for diversified, risk managed exposure to China’s onshore markets will most likely opt for finding an experienced trader with an impressive track record to manage the portfolio, as opposed to the work, time, and increased risk of underperformance involved in learning the ropes of China A-shares. This is where DIY plans will hit their most serious snag. As mentioned above, the average China portfolio manager has 2.6 years of experience. With increasing liberalization of financial markets, the industry is taking off, and good analysts and managers are in understandably short supply, the best and brightest understandably preferring to fast track with top national, if not global, firms.

A THIRD WAY: TIRITH MULTI-THEMED, MULTI-MANAGER, SEPARATELY MANAGED ACCOUNTS

We won’t deny that we present the above as a somewhat more than an objective breakdown, and to infer that trying to set up shop for institutional direct investment into Chinese stocks is quite an involved and potentially costly project, with extended learning curves and associated risks.

Nonetheless, we still believe in the long term upside of China’s evolving capital markets strongly enough that we launched Tirith, in order to make such institutional, direct investment as streamlined and customized as possible. In effect, we’ve created a platform of the best providers and money managers China has to offer. Combined with our facilitation expertise, we provide the best of both worlds: customizable portfolios overseen by the best money managers to international standards.

Our Product:

We’ve instituted a fully-compliant process by which foreign institutional investors can inject USD into our offshore, QFII licensed entity, further to which we will set up on shore separately managed accounts, with the aforementioned CITI as custodian and CICC as prime brokers, GuoTaiJunAn as execution brokers, Ernst & Young as auditors, and Fosun-associated Topsperity as onshore advisors.

This ecosystem of best-in-class providers has been assembled under the auspices of Allen Kuo, an executive president at Fosun & Tirith’s investment manager/chairman. With over 20 years’ experience in cross-border investment, including head of Asia securities for Deutschebank, setting up one of the first PFMs in China via PingAn Russell, and serving as CIO of Noah Group, Allen believes with the rest of us that the time is perfect for inbound investment, for those who

1) share our China conviction,

2) seek true global equities diversification with a large and liquid, but uncorrelated market,

3)wish to capture the outperformance possible in this inefficient, mostly retail-traded market

4) want early participation in the long-term growth of a market essentially in the same place as China’s economy was 20 years ago, just beginning to remove its barriers to entry, with full government support for internationalization.

Of course, a market and economy facing the risks addressed above, demands a heavily risk-managed approach. To ensure investors have both a customizable portfolio, and the best in risk management, we are structuring the SMAs as manager-of-manager funds, with China fund veteran Allen Kuo overseeing a group of managers we can truly call best-in-class:

All managers, including Allen, have a long-term capital preservation/appreciation approach to investing, and have remained successful over the long term by acquiring the .kills and discipline of risk-management as called for in China’s stock markets, including a heavy emphasis on policy research, government networking, and taking action at the first sign of regulatory headwinds.

To the point of regulatory/policy risk, we have retained the advisory services of Qi Ge, founder of China’s first fund of funds, Diligence Capital. More importantly, Mr. Ge wrote much of the Chinese law governing both private fund investment and QFII regulations. As such, he is still very much in the loop of government deliberation over new regulations and policies, and advised Tirith accordingly.

CONCLUSION:

In all, we hope to have made our position on China’s investability clear, why we view China’s domestic capital markets as one of the great growth stories of the next decade, and why its A-shares markets represent a highly investable option for uncorrelated equity diversification.

External factors, chiefly ongoing tensions in the wake of China’s growing influence and its effects on America’s spheres of influence, fuel an asymmetrical narrative that frames China’s macro drivers and current financial legislation in a distorted light. That distortion may prolong the participation of less objective, research-oriented investors in the internationalization and growth of China’s domestic markets, but it will not prevent that growth, in our view.

Of course, the participation of the foreign retail investor in this new growth. Institutional investors taking extant passive approaches to China’s domestic markets face limitations in both opportunity set and risk management. Those who would invest directly face extensive set-up & operational costs, and the prospect of building a network for access to optimal providers.

Those limited options for participation are the reason for Tirith’s creation, a firm that streamlines foreign institutional investment, and provides the most experienced, successful portfolio managers in China. If you have China conviction, we have the access.